Know your (CS and tech) history

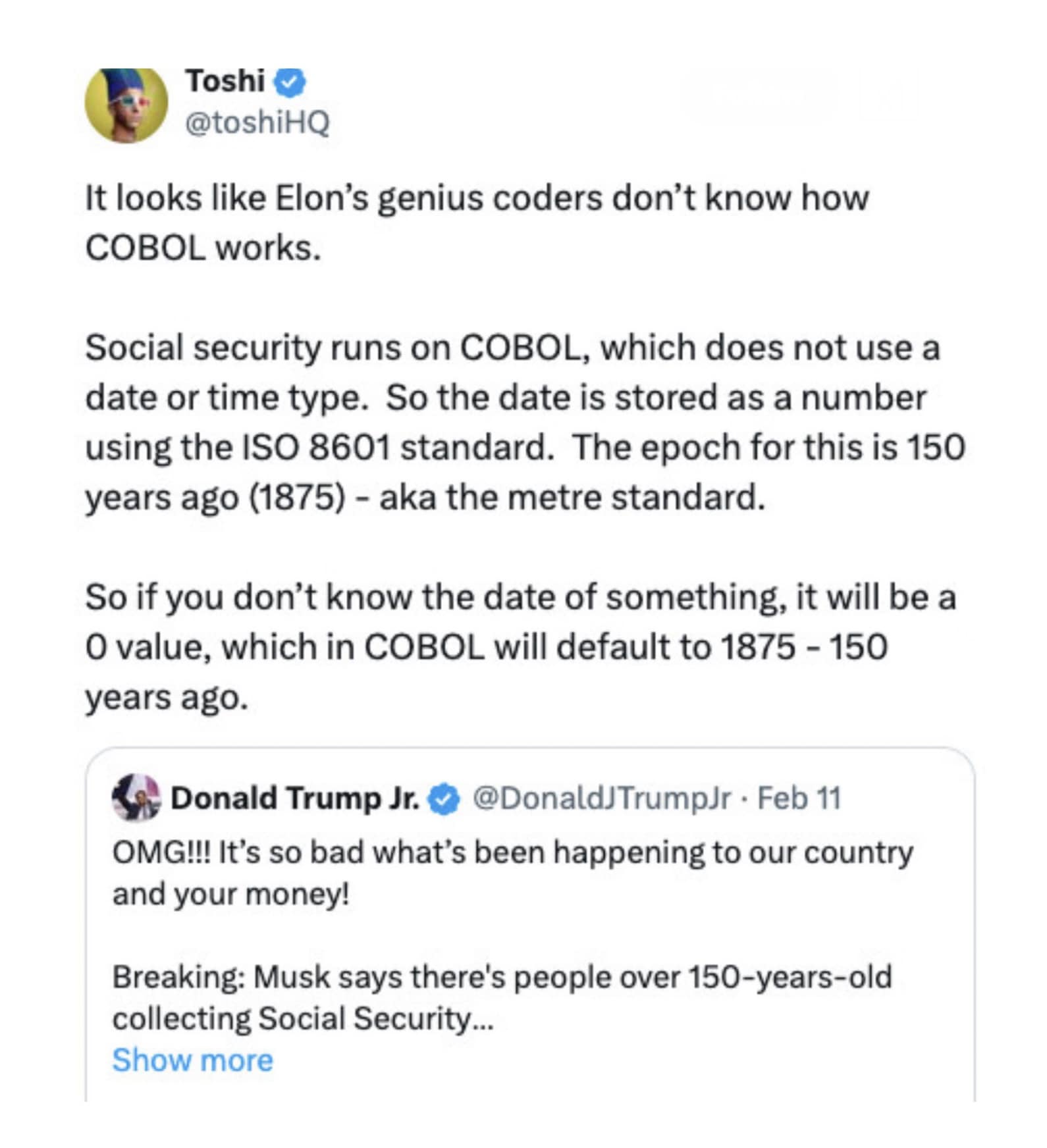

On Friday I saw this post shared by a couple of friends of mine.

Why did Musk and Trump make these false claims? Ignorance? Stupidity? Malice? Well, with the current Republican party, usually it's a combination of all three.

But wait, should I just be accepting Toshi's post explaining what's going on? I usually don't accept random posts as facts. Well, in this case, it was posted independently by a couple of friends of mine who are knowledgeable, smart, and also don't blindly share posts they can't confirm as fact.

And then, there's the fact that this makes sense to me given when I know about computing and computing history.

If one looks up the [[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISO_8601 ][ISO9601]] spec, indeed the Epoch for the standard is May 20, 1875, 150 years ago.

This isn't strange. I mean, the Unix Epoch is January 1, 1970. That is, Unix systems tracked time by the number of non-leap seconds since 1/1/1970.

Using a time representation like this can have some interesting effects and consequences. Uninitialized dates appearing to be 150 years ago being one of them. On the Unix side, the time has typically been stored in a 32 bit number. With 32 bits, we'll hit our largest time, or maximum date early in 2038 at which point, the calendar will roll over back to 1/1/1970. This is known as the 2038 problem and it's not good. Now, this problem might be averted if by then all systems use a 64 bit representation for the time and date but I wouldn't hold my breath. I mean, the systems which falsely show "150 year old people" are cobol systems probably written before the first second of the Unix epoch.

Another similar time/date problem was the Y2K problem. That's when computer systems written prior to the year 2000 used 2 digits to represent years, I mean, who'd still be running a program that long that it would cross over into the 2000s. Well, it turns out quite a few. This caused a big stir in the late 1990s. To the outside world though, 1/1/2000 came and went and it seemed like it was a big nothing but the truth is, a lot of people put in a lot of time behind the scenes to fix the problem.

Now, all three of these example could be problems or might not be problems but if you know a bit of your computing history then you'll understand what's going on and won't fall for the lies and misdirections hurled by Musk and if you're a tech person, you'll be able to deal with them should they occur in your day to day.

These artifacts of history appear all over. Here are a couple more of my favorites.

Using a single letter variable i as a counting variable in a

loop. There's a school of thought that says you should never use

single letter variable names - they should always bee clear full word

labels. Using i for a loop index is unclear.

I saw a argument discussion of this online a few months ago.

Now, you could use something like index for your loops and in fact you

could use text completions so you only have to hit i but personally, I

think having things too long is just as bad as too short.

I see nothing wrong with using i for a loop and understanding the

history helps give context.

In early programming languages, you could only use variable names of limited lengths. For example, in Fortran IV, a language I used early in my career (even though it was well out of date by the time I learned it), variables only had 6 significant characters. I also used a version of BASIC that only supported 2 characters.

That is, in that version of BASIC, you could have variables named

index, indecisive, and in and they'd all refer to the same

variable. Everything after the second character was ignored. Fortran

IV gave us more characters but was still limited.

Then, add to that, in Fortran IV, variables that started with the letters i,j,k,l,m, or n were integers. Start with any other letter and the variable was floating point.

So, in this context, using short variable names made sense and using i

as a counting variable or index for a loop or array made even more

sense.

To me, at this point, it's an idiom in programming and makes for concise lines and when scanning code, it's easy to read confirm your loops are okay. It also makes the longer word length variables that live beyond your loops stand out so in my opinion it's a win win.

Sticking on the Fortran IV kick, let me talk about JCL - job control language used on big iron, that's IBM mainframes to you.

When I was at Goldman Sachs. before I started my teaching career, I was friends with some Cobol programmers. They would complain about the arbitrariness of JCL. I don't know exactly how they worked but it seems that before they could submit their cobol programs to run, they had to submit a JCL program right ahead of it to tell the mainframe about the forthcoming cobol program and how to deal with it.

They complained how certain things had to be in certain columns and how the entire process was incredible rigid.

Now, this was around 1989 so they were all programming on "modern" terminals. I started talking to them about this and they showed me some JCL and I immediately got it.

It's what I used on punchcards back at Stuy when I learned Fortran IV on our IBM 1130. I had no idea I was using JCL but I had to make a few special punchcards with very specific instructions and put them at the top of my program deck - all the cards that represented my fortran program.

Well, that was JCL.

The column specifications made instant sense to me. A punchcard had 80 characters and the reader was set up to read all 80 characters at once.

It made all the sense in the world to put column specifications and restrictions on the language given that it was for punchcards. In the 1980s and beyond the punchcards had gone away but JCL lived on.

I explained this to my friends and they got it. Didn't make JCL any less annoying but they were then able to better grok the system.

Another one is tar - the Unix archive system and zip - used by Windows.

A Zip file (and its later more modern counterparts) takes a bunch of files, compresses each one and the combines all of them in an archive. The Unix tar command combines all the files, uncompressed into an archive then you typically compress it with a program like gzip.

Each of course, has it's advangate. Since you compress tar files after combining them, your compression program can exploit similarities between the files in the archive. On the other hand, zip files allow you to easily extract any individual file without having to uncompress and unbundle the whole kit and caboodle.

Why the difference? I don't know why zip was defined the was it was but tar was a historic reason. Tar stands for "Tape archive." Hard drives were small at the time and backups were typically stored on tape which was cheap and big. The thing with tape though is that it's linear - no random access so you'd just send all your files one after another to the archive. You can do that if you're not compressing but not if you are. Later, when tar files were stored on disk drives, people started compressing.

Another and one of my favorites goes back to that religious war - Emacs vs Vi(m). I'm an Emacs used but see nothing wrong with Vi(m) but I get really annoyed when Vim users start talking about how Vim is inherently more efficient. It's modal design and using the h,j,k, and l keys were chosen to be faster.

I get annoyed becuase the people making those claims don't understand history. They're also wrong. Modal editing is not inherently faster and as a lefty I can say that using the h,j,k, and l keys are not optimal for me. Of course, if Vim works for you and is more efficient for you personally, that's great.

The thing is, the Vim design is from history. The modal thing comes from Vi being built out of a line editor. It was a Vi-sual interface to a line editor. The keys? Well, it happens that when Bill Joy wrote Vi, he was working on a keyboard that had the arrow keys inscribed on the sides of the h,j,k, and l. Back then, people were using much slower computers, frequently using slow modems or even teletype terminals. Blinding cursor movements were not high up on design decisions.

I actually made a 35 minute video on Emacs vs Vim that goes into the history. You can view it here if you're interested.

Now, the tar vs zip and Emacs vs Vim and even the i as a variable

thing aren't really important, at least knowing the history isn't

important but the date stuff is, particularly with Musk weaponizing

lies about it.

On the other hand, the more of this history you know, the more you understand why things are the way they are.

As a whole, we do a pretty poor job teaching CS and Tech history. There have been some efforts recently to do better but they're mostly based on the people. Specifically on CS history from members of underrepresented populations. This is all good - it's important and I'm on board but adding technical history is also important.

Personally, I wish I knew more of it.